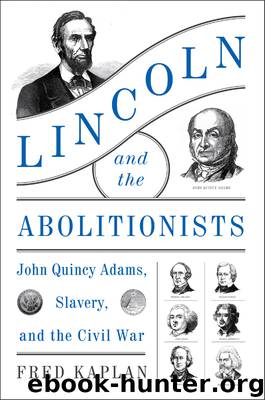

Lincoln and the Abolitionists by Fred Kaplan

Author:Fred Kaplan

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780062440013

Publisher: HarperCollins

Published: 2017-05-06T04:00:00+00:00

SEVEN

The Constitutional Rag

At 5:00 P.M. on a cold Saturday in March 1848, the remains of John Quincy Adams were interred in a stone vault in Quincy, Massachusetts. It was in a cemetery he had wandered in many times, meditating about time and transience. Across the street, in the church whose construction the former president had funded, the Reverend W. P. Lunt had memorialized Quincy’s famous son to a full house of distinguished mourners. By late afternoon, the day had been exhaustingly long for the participants. The procession to the church had been slowed down, the sun having turned frozen roads to mud. Adams’ only surviving child, Charles Francis, thought the sermon “elegant and happily conceived.” The text from Revelation, “Be thou faithful unto death, and I will give thee a crown of life,” had to seem to the five hundred or so mourners deftly appropriate. At such a moment, everyone would have been moved by the sentiment.

The only body fully at rest had started its journey from Washington earlier in the week. For the first time in American history, a nation in mourning paid its respects to a dead ex-president traveling by shrouded train from the nation’s capital to his grave site. The journey ascended entirely through a Northern landscape, as befitted the man in the coffin. In Philadelphia, the body was displayed for two days in Independence Hall. It was remarked that the spirit of his father’s presence was palpable. Then, with mourners lining the tracks, the special train slowly moved on to Boston. The next morning, an assemblage of city and state officials, the delegation from the state legislature, and representatives of both houses of Congress, accompanied by honor guards and militiamen, marched to the railroad station. Special trains of the Old Colony Railroad took them to Quincy. Joined by members of the Adams family and townspeople, organized into a procession they marched “to the Adams mansion,” Peacefield. At a quarter past two, the funeral cortege moved toward the Unitarian church. The Roxbury artillery fired minute guns. “By three o’clock all in the procession were seated in the church.”

It was a nonpartisan assemblage. Not everyone shed tears. Still, it was a momentous occasion, partly local, partly national. The House of Representatives, narrowly controlled by Adams’ party, had sent a delegation of thirty members, one from each state in the union, evenly split between Whigs and Democrats. The more widely publicized national funeral had occurred in Washington on February 26, three days after the eighty-one-year-old Adams died. His body had lain in state in the House Rotunda, its coffin lined with lead, his face “visible through a glass.” Amid funereal pomp, after a service more impressive for its assemblage than the sermon, the corpse was taken to the congressional cemetery for temporary burial. The elite of the three branches of government, dark in Victorian mourning dress, followed the cortege. President Polk noted in his diary that it had been “a splendid pageant.” Official Washington had self-consciously created a historically memorable spectacle.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15324)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14476)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12363)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12081)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12012)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5765)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5423)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5394)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5293)

Paper Towns by Green John(5174)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4994)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4946)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4484)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4481)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4433)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4382)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4333)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4303)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4186)